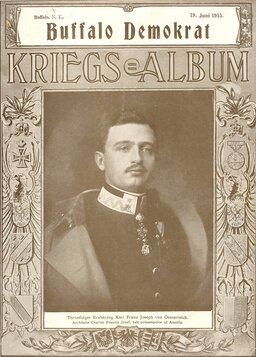

Long before America went “over there,” Western New York had to cope with some unique realities in the opening years of the First World War. In part one of a three-part series, we look at a usually peaceful region during the years of true neutrality.

Buffalo and the Great War, Part I: The War Before the War

The full content is available in the Summer 2015 Issue, or online with the purchase of:

If you have already purchased the product above, you can Sign In to access it.

Related Content