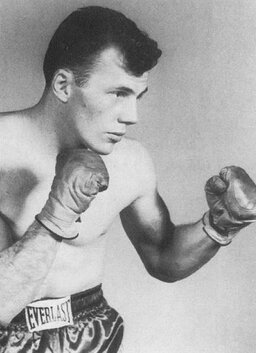

A boy's dream turns to golden history with amateur boxing during the 1950s.

Midcentury History in the Golden Gloves

The full content is available in the Fall 1998 Issue, or online with the purchase of:

If you have already purchased the product above, you can Sign In to access it.

Related Content