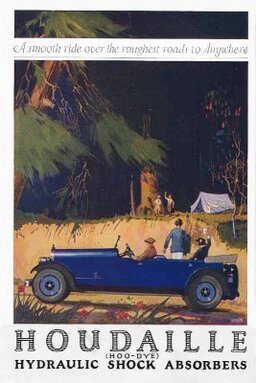

Beginning with shock absorbers, the history of Houdaille Industries, in its various guises, encompasses everything from auto parts to launch pads for spaceships-- and just about everything in between.

The Houdaille Story

The full content is available in the Spring 2020 Issue, or online with the purchase of:

If you have already purchased the product above, you can Sign In to access it.

Related Content