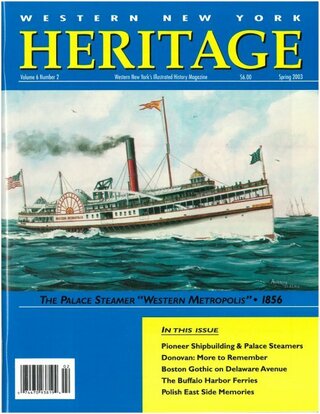

Memories of growing up on Buffalo's East Side in the 1940s-50s.

A Place for Lost Time: A Look Back at Buffalo's Polish East Side

The full content is available in the Spring 2003 Issue, or online with the purchase of:

If you have already purchased the product above, you can Sign In to access it.

Related Content