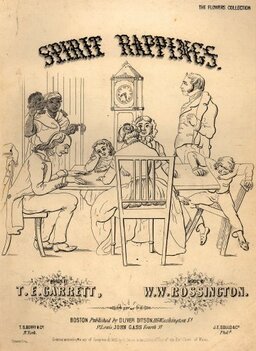

The infamous Fox sisters are no strangers to our pages. But here we focus on the team of Buffalo doctors who came very close to cracking the case of their mysterious "rappings."

Buffalo Ghostbusters: Doctors, Mediums and an Examination of the Spirit World

The full content is available in the Spring 2016 Issue, or online with the purchase of:

If you have already purchased the product above, you can Sign In to access it.

Related Content