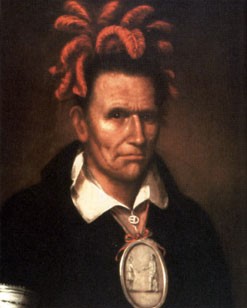

John Lee Douglas Mathies portrait of Red Jacket., featured in the Fall 2004 issue of Heritage Magazine.

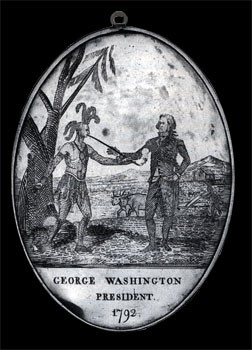

Red Jacket, whose Indian name was Sa-Go-Ye-Wat-Ha, is well-known in Western New York as a great Seneca orator. During the Revolutionary War, he sided with the British, who gave him a red coat which gave him his English name. When the second war for independence began, however, Red Jacket persuaded his people to remain neutral. In 1792, when he traveled to the U.S. capitol in Philadelphia to present the claims and grievances of the Iroquois, President George Washington presented him with the solid silver peace medal, above. Red Jacket greatly prized it and wore it whenever his portrait was painted.

The Peace Medal given to Red Jacket. Silver, 5 x 7 inches. Several generations after Red Jacket's death, his descendants presented it to the Buffalo & Erie County Historical Society.

Red Jacket retained great influence through his life in his home community of the Buffalo Creek reservation (now part of the city of Buffalo). Always a passionate defender of the traditional ways and religion, he struggled with the white settlers and their governments over the loss of land. He also saw his own people becoming Christian and adopting the ways of white people, which he interpreted as the signalling the end of the Indian culture. Near the end of his life, he said, "...when I am gone, and my warnings shall no longer be heard, or regarded, the craft and avarice of the white man will prevail...my heart fails, when I think of my people, who are soon to be scattered and forgotten."

Red Jacket is reported to have said on his deathbed, "..white men will come and ask you for my body. They will wish to bury me. But do not let them take me...bury me among my people." He also directed that services for his burial could be conducted as his Christian wife wished, and so he was buried in the Indian cemetery near the Christian mission church in Buffalo Creek following his death on January 20, 1830. Comedian Henry Placide had a marble slab erected over his grave which was steadily eroded by souvenir hunters and vandals who chipped pieces from it. He and the other Indians buried there were not to rest undisturbed, however. The Buffalo Creek Treaty of 1842 eliminated the Buffalo Creek reservation and the cemetery grounds were encroached by white burials and settlement. By 1851, some Buffalonians were talking about moving the remains of Red Jacket from the Seneca Indian cemetery.

Charles E. Clark, one of the original proprietors of Forest Lawn Cemetery, proposed a tribute at Forest Lawn to the Native Americans who aided America during its wars for independence. Forest Lawn historians suggest that his purpose in proposing this may have been to secure a celebrity burial and so generate sales of burial plots. This offer of land for burial of Indian remains was later accepted by the Buffalo Historical Society.

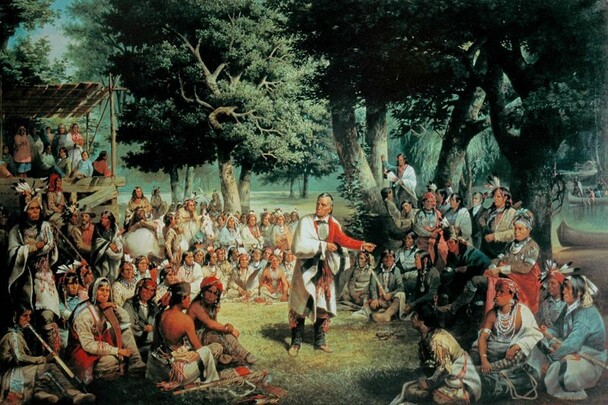

"Trial of Red Jacket" painting by John Mix Stanley. Centerspread reproduction in the Summer 2004 Heritage Magazine. Image source: Buffalo & Erie County Historical Society.

In 1885, the Buffalo Historical Society recorded everything related to the removal and reburial of Red Jacket's remains and other Senecas by publishing an entire volume dedicated to Red Jacket. In the introduction they said, "The project of re-interring the remains of Red Jacket and of contemporary chiefs, lying in neglected graves in the vicinage of Buffalo, has for a score of years been discussed and advocated by prominent members of the Buffalo Historical Society. In public addresses, on different occasions, Messrs. Lewis F. Allen, Orlando Allen, Orsamus H. Marshall, William P. Letchworth and others have, in earnest and touching language, urged the measure as a fitting and pious duty toward the distinguished chiefs and leaders of the hapless aborigines whom we have dispossessed...On the twenty-ninth day of December, 1863, the late Chief Strong...delivered a lecture, the theme of which was Red Jacket. He concluded with an eloquent appeal, addressed to his white brethren, to rescue the remains of Red Jacket and other eminent chiefs from threatened profanation and bury them in Forest Lawn Cemetery."

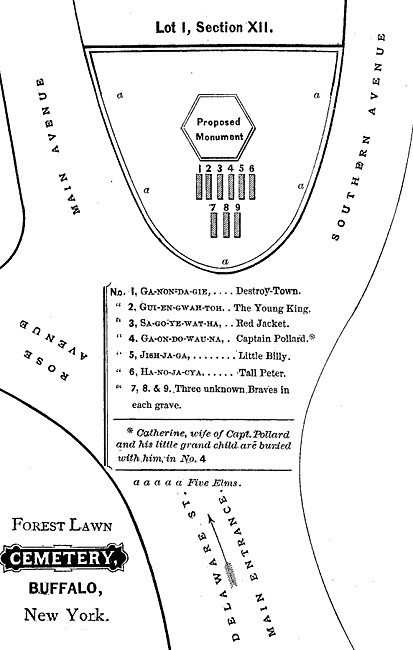

Diagram of the plot referred to as the "Buffalo Historical Society Plot" at Forest Lawn. The location of Section 12 is immediately inside the Delaware entrance.

Red Jacket, Transactions of the Buffalo Historical Society, 1885

No action resulted from this speech and it was not until 1876 that William C. Bryant, member of the Historical Society Board of Councilors and persistent defender of the Senecas, visited the Cattaraugus Reservation and presented the subject to the Council of the Seneca Nation. That body approved the project.

In 1879, the Historical Society obtained the remains of Red Jacket from Humphrey Tolliver, unofficial sexton at the Seneca Indian Cemetery, and placed them in a plain pine box. The remains were stored in the vault of the Western Savings Bank until the re-interment project came to fruition in 1884.

The Historical Society formed a committee in early 1884 to raise funds for the large task; they were able to obtain subscribers to pay for the foundation for the statue above, erect headstones for others reburied, pay all expenses for the Indian delegates and for the ceremonies held October 9, 1884.

Details of the excavations at Seneca Creek by the Historical Society:

The Committee on Selection of Indian Chiefs for Interment made several visits to the old mission cemetery... accompanied by the venerable missionary, Mrs. Wright, and by aged Indians who had been long familiar with the locality, some of them related to Red Jacket by ties of blood or marriage. The leading men of the Senecas, before removal of the tribe from the Buffalo Creek Reservation, lay in graved excavated in a small elevated area, at or near the center of the cemetery. The earth there is a dry loam. The graves were two or more feet deeper than it is the practice now to dig them. The uniformly faced the rising sun. Notwithstanding this sacred spot is the property of the Indians, consecrated to the repose of their dead and those of their faithful missionaries, it has been invaded by the whites, who have buried their deceased friends there in considerable numbers. It was found necessary to tunnel under many of these surreptitious graves in order to rescue the red proprietors who slumbered beneath the strange intruders. About forty graves in all were opened, and all the work was done under the supervision of Henry D. Farwell, Esq., the undertaker. Few, if any, articles were found with the remains, save an occasional pipe and the decayed fragments of blankets, broadcloth tunics, silken sashes and turbans, and beaded leggings and moccasins. Exception should be made in the instance of a very young child, whose little head was enwrapped in a voluminous silk hankerchief. In a silken knot close to its ear was a tiny, neatly-carved rattle of bone, and on its breast, above the little folded hands, was a small and pretty porcelain drinking cup. But seven of the skeletons could be positively identified, namely those of Young King, Destroy Town, Captain Pollard, his wife and his granddaughter, Tall Peter, and Little Billy, the war chief. Nine others, doubtless the remains of warriors famous in their day, were exhumed, buried with them at Forest Lawn, and will be designated as the undistinguished dead. The work of exhuming and re-intering the tenants of graves in other neglected Indian burial-grounds is contemplated, but was temporarily postponed for valid reasons.

The ceremonies for the re-interment of Red Jacket and the other remains were carried out over two days. On Wednesday afternoon, there was a viewing of the remains at the Historical Society by the invited Indian guests, among whom numbered forty chiefs and sachems from the Onondaga, Delaware, Oneida, Tuscarora, Seneca, Cayuga, and Mohawk tribes in the United States and Canada.. Afterward, the remains were placed in 6 polished oak caskets with silver trimmings. On Thursday, October 9, a funeral procession of six hearses and 75 carriages made its way from the Historical Society on Main Street to Forest Lawn where a great crowd was gathered. As described in the Buffalo Historical Society's "Red Jacket" publication, "The scene was a strange, solemn and impressive one, and will not be soon effaced from the minds of those who witnessed it. The packed stand, with the Indians in bright-colored garb prominent in the foreground, the empty graves, ready to receive the polished oak caskets with their precious contents, the thousand or more faces of those crowding around, and the array of vehicles of every description -- all this went to make a unique and picturesque scene."

The invocation and benediction were given by Native American Christian ministers in their native tongues. Indian songs and dirges were interspersed with speeches by William Clement Bryant of the Historical Society, and Chief John Jacket, a Seneca sachem, who gave a speech in the Seneca language.

That evening 3,000 gathered in the Music Hall to hear additional speeches, including one given by Native American General Ely Parker, adjutant to General U.S. Grant during the Civil War. (He died in 1895 and two years later his remains were exhumed and brought to Forest Lawn, where they lie today.)

The statue of Red Jacket was erected atop the granite base in 1891, after funds were raised. The bronze statue shows Red Jacket dressed in his embroidered red jacket, wearing the silver peace medal given to him by George Washington, poised as if to continue an oration.

The Seneca Indian Cemetery was saved from development in 1909 by John D. Larkin, who purchased the land and donated it to the city of Buffalo as a park. The story of this piece of land, repeatedly neglected and saved, can be found in the Fall 2004 issue of Heritage Magazine, copies of which are available for purchase.