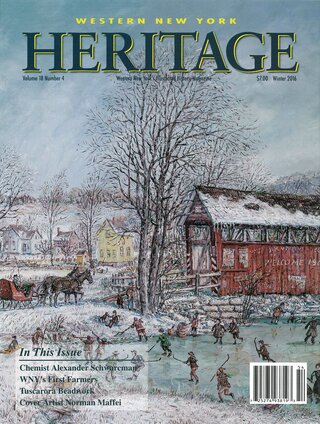

Niagara Falls had been a trade center long before the falls became world famous. As tourism in the region grew, so did the demand for the beautiful beadwork made by the Tuscarora Artisans.

Tourism, Trade and Tuscarora Beadwork at Niagara Falls

The full content is available in the Winter 2016 Issue, or online with the purchase of:

If you have already purchased the product above, you can Sign In to access it.

Related Content