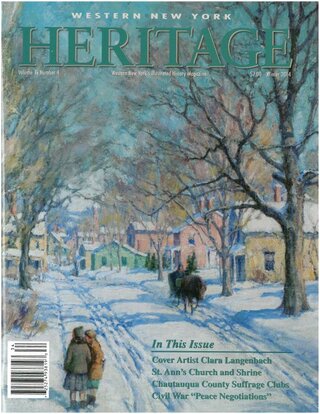

In the late 1800s, crusaders in Chautauqua County led a movement by launching the state’s first county suffrage association, influencing public sentiment and hosting several highly attended pro-suffrage events.

Women’s “Banner County”: Chautauqua County and the Suffrage Movement

The full content is available in the Winter 2014 Issue, or online with the purchase of:

If you have already purchased the product above, you can Sign In to access it.

Related Content